Table of Contents

Fibre And Transit Time

Soluble vs Insoluble Fibre

Increase Fibre Slowly

Fibre Supplements & IBS

Increasing Fibre With IBS-C

Fibre Content Of Different Foods

Can I Eat Too Much Fibre?

Phytic Acid And Fibre

Levels Of Phytic Acid & Phytase in Foods

How To Reduce Phytic Acid

Soaking To Reduce Phytic Acid

Do You Really Need To Reduce Phytic Acid?

Health Benefits Of Phytic Acid

Health Benefits Of Fibre

Further Reading And References

Fibre And Transit Time

In a study, for those with a gut transit time greater than 48 hours, all types of fibre reduced or normalised delayed transit time. However, for those with a transit time of less than 48 hours, fibre did not accelerate normal transit time. (3)

The type of fibre required for IBS depends on the type of IBS that you are suffering from.

Soluble vs Insoluble Fibre

- Soluble Fibre (for diarrhoea)

- has a slowing effect on the digestive tract helping with diarrhoea

- attracts water helping to remove excess fluid decreasing diarrhoea

- dissolves in water, becoming a soft gel

- readily fermented

- recommended for those suffering from diarrhoea with food sources including:

- apples

- oranges

- pears

- strawberries

- blueberries

- peas

- avocados

- sweet potatoes

- carrots

- turnips

- oats

- oat bran

- barley

- beans

- Insoluble Fibre (for constipation)

- speeds up the digestive tract helping to alleviate constipation

- does not dissolve in water, keeping intact through the digestive system, helping to bulk out stools, similar to a laxative effect

- poorly fermented

- recommended for those with constipation with food sources such as:

- courgette (zucchini)

- broccoli

- leafy greens

- cauliflower

- blackberries

- flaxseed

- chia seeds

- whole grains

- bran

- brown rice

- cereals

- rolled oats

- cellulose (found in legumes, seeds, root vegetables, and vegetables in the cabbage family)

Note that many of the foods mentioned above contain FODMAPs so it will depend on your individual tolerance to that food. Consequently, you may only be able to consume a specific quantity of that food or none at all depending on symptoms.

Increase Fibre Slowly

Consuming far more fibre than you are used to all at once can make you bloated and gassy since your body has not had a chance to adapt to the increased intake.

To increase fibre to aid IBS symptoms, it is recommended to add fibre one meal at a time, wait a few days to a week and keep a food diary of how your body is reacting, then continue to add in this way all being well.

Consider each meal and decide where fruits and vegetables can be incorporated. For example, Greek yoghurt with fruit, nuts and flaxseed for breakfast instead of pastry. Salads, sides of fruits and vegetables with whole grains like brown rice and quinoa can be included with lunch and dinner. Ideally half your plate should contain fruits and vegetables. Instead of refined grains such as white bread, refined cereals and white rice, choose whole-grain bread, bran muffins, oatmeal, whole grain cereals and brown rice. Again, make these changes gradually. Note that any increases in fibre must include increases in water consumption for the fibre to do its job – otherwise it could cause more gastrointestinal distress. (1)

If fibre causes gas, flatulence, distension, bloating or pain, this is more likely to be due to insoluble fibre, rather than soluble. (3) However, the opposite may be true for some people, so it is a case of trial and error. Note that some fibre sources have both soluble and insoluble fibre such as oat bran, psyllium, and soy fiber. Additionally, different fibres have different speeds of digestion and some people may be tolerant to highly fermentable fibres, though others may not be. Less fermentable fibres increase faecal weight the most, especially cereals (oats, rice bran, whole-grain pasta and whole-grain bread) and vegetables (3). This again confirms the need to try different types of fibre. It is to be noted that by-products from fermentation are beneficial to health. (2)

IBS-C patients can benefit from a wider variety of fibre sources, particularly those that are less fermentable usually found in cereals. However, if gas related symptoms are a problem, soluble rather than insoluble fibres may be more beneficial. (3)

A comparison of the amount of insoluble and soluble fibre in different foods can be found here: (52).

Fibre Supplements & IBS

| IBS Symptoms | Fiber Treatment |

|---|---|

| Lower abdominal pain | Methylcellulose or Psyllium |

| Upper abdominal pain | Oatmeal, Oat bran, or Psyllium |

| Constipation | Methylcellulose or Psyllium |

| Incomplete evacuation | Methylcellulose or Psyllium |

| Diarrhea | Psyllium or Oligofructose |

| Excessive gas | Methylcellulose or Polycarbophil |

| Fibre supplement type | Recommendations for use in people with IBS |

|---|---|

| Psyllium | Appears to be well tolerated by many people with IBS. Studies indicate that it may be especially useful in relieving constipation in people with IBS-C. However, psyllium may not be tolerated by all. |

| Wheat bran*4 | Existing studies suggest that wheat bran is ineffective at normalising bowel movements and may worsen symptoms in people with IBS. |

| Oats/oat bran | May improve constipation, abdominal pain and bloating in people with IBS, but more studies are needed. |

| Linseeds/linseed meal | Up to 2 tbs/day may improve constipation, abdominal pain and bloating in people with IBS, but more studies are needed. |

| Wheat dextrin | Has not been formally studied in IBS. |

| Inulin | Highly fermentable and may worsen gas related symptoms in people with IBS. |

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS)/galactooligosaccharides (GOS) | Rapidly fermentable and may worsen gas related symptoms in people with IBS. |

| Resistant starch | Slowly fermented along the whole length of the large intestine, so may produce less gas related symptoms than other highly fermentable fibres (e.g. FOS, GOS and inulin) in people with IBS. Has prebiotic properties, but is not necessarily helpful for normalising bowel movements. |

| Partially hydrolysed guar gum*1 (PHGG) | Existing studies indicate that PHGG may be well tolerated and helpful in people with both IBS-C and IBS-D, but more studies are needed. Has prebiotic properties, which may be beneficial for gut health. |

| Methylcellulose*2 | May be especially helpful in IBS-C as it is non-fermentable and has gel-forming properties that help with stool softening. More studies are needed to confirm these proposed benefits. |

| Sterculia*3 | May be especially helpful in IBS-C as it is non-fermentable and has gel-forming properties that help with stool softening. More studies are needed to confirm these proposed benefits. |

*1 Optifibre contains PHGG

*2 Cellulose: In a study, due to its insoluble nature and the sizes of micronised cellulose particles, microcrystalline cellulose caused fewer symptoms than ispaghula (psyllium) and guar gum. (51)

*3 Normacol contains Sterculia. The other ingredients are sodium hydrogen carbonate, sucrose, talc, titanium dioxide, hard paraffin and vanillin. Note that talc may be contaminated with asbestos (further information here and here).

*4 Slow transit constipation (STC) is related to an issue with nerves and muscles slowing the movement of waste through the large intestine. In these cases, adding stimulating bulking agents such as bran may increase the workload of the gut causing irritation and reactions. If this is the case, dried fruits such as apricots, figs and prunes may help due to their soluble fibre content, which turns to a gel binding with waste and assisting with the softening of stools. Since insoluble fibre adds bulk to an overly full system, this could cause discomfort. (11) As always this is down to individual tolerance and some people will have no issue with bran or insoluble fibre.

Increasing Fibre With IBS-C

| Food | Comments |

|---|---|

| Vegetables | ·Where possible, consume with the skin on ·Include a variety of colours each day ·Eat at least 3 different vegetables per day ·Spread vegetable intake over at least 2 meals/snacks |

| Fruit | ·Where possible, consume with the skin on ·Eat a variety of colours ·Eat two serves per day (a serve is roughly the size of your fist) |

| Wholegrains | ·Choose cereal products (breakfast cereal, cracker, bread, pasta, etc.) based on a variety of wholegrains (for example, sorghum*1 or oat breakfast cereal, spelt*2 sourdough bread, brown rice cracker and quinoa pasta ·Read the ingredients to determine which grain is in the product (remember, ingredients are always listed in quantity from most to least) |

| Nuts and seeds | ·Eat daily via whole nuts and seeds, 100% nut spreads and ground nuts/seeds (e.g. LSA) |

| Legumes | ·While many legumes are high FODMAP and best avoided during the initial strict phase of the low FODMAP diet, there are some low FODMAP options including firm tofu, ¼ cup tinned chickpeas and ½ cup tinned lentils are low FODMAP . Aim to include legumes at least 1/week in your diet |

*1 Sorghum is gluten free and contains more insoluble fibre than soluble fibre. Sorghum can be found in Nutribrex breakfast cereal. Nutritional information for sorghum can be found here: (53). The table below shows a comparison of the insoluble and soluble fibre content of Sorghum compared to other breakfast cereals:

| Food | Amount | Total Fiber (grams) | Insoluble Fiber (grams) | Soluble Fiber (grams) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Bran (Arrowhead Mills) | 1 cup | 27.40 | 25.20 | 2.20 |

| Sorghum | 1 cup | 26.50 | 18.50 | 8.00 |

| Oat bran | 1 cup | 5.70 | 3.00 | 2.70 |

| Shredded Wheat (Nabisco) | 1 biscuit | 2.30 | 1.90 | 0.40 |

| Weetabix (Weetabix) | 1 cup | 2.00 | 1.70 | 0.30 |

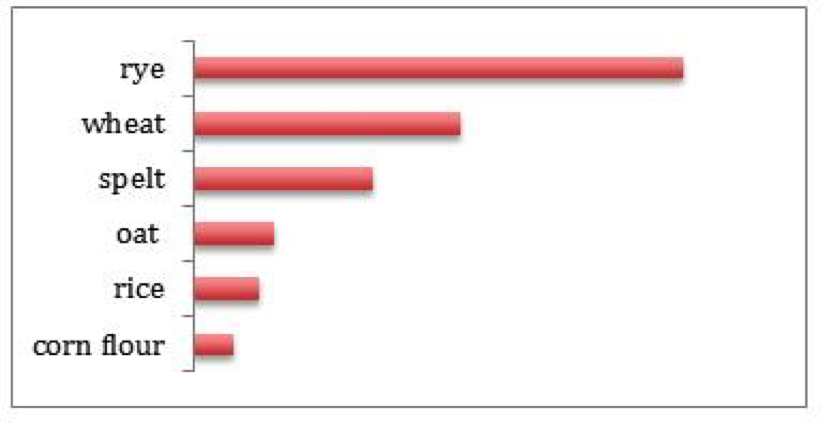

*2 Information about spelt can be found here: (54). Although a distant relative of wheat, spelt is sometimes more easily digested, like oats, having lower gluten content than traditional wheat (56). Monash University found that the FODMAP content of spelt is lower than modern wheat, though both are higher in FODMAPs than gluten-free flours such as rice, cornflour and oat. The below table from Monash University compares the FODMAP content of common flours:

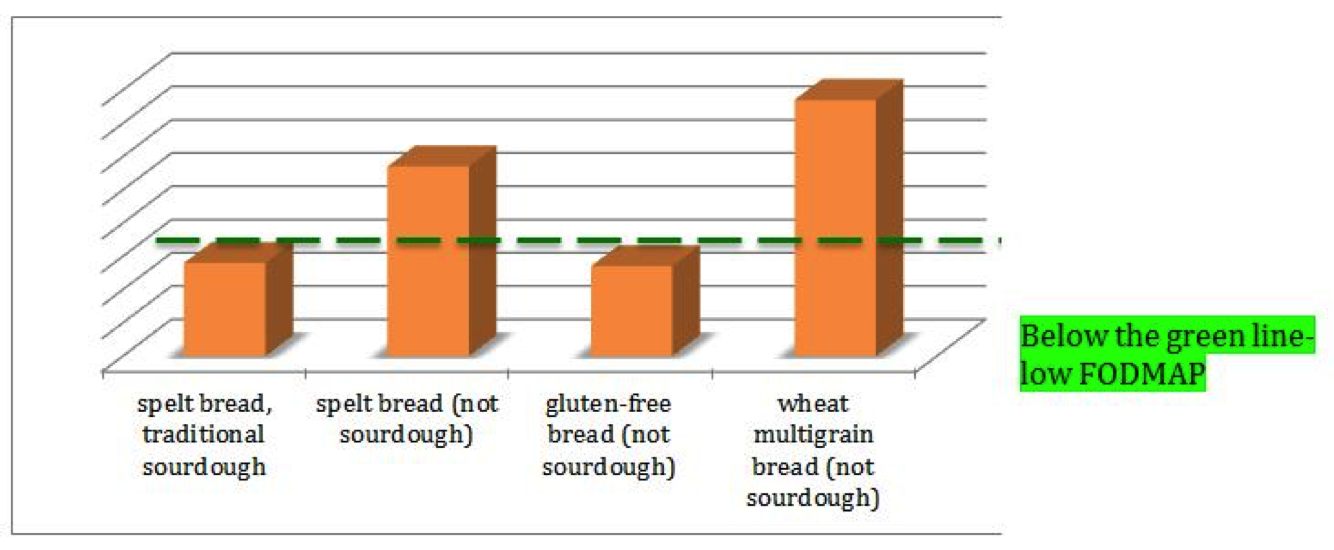

The amount of processing that food undergoes will have a major impact on FODMAP levels in foods. The Monash University table below shows the total FODMAP content of one serve of bread: spelt, wheat and gluten-free:

Cooked spelt pasta is low FODMAP at 74g serving:

Fibre Content Of Different Foods

The following articles discuss high fibre foods including tables with the amount of fibre in specific foods: (5), (6), (7), (8) and (9). This article contains the Low FODMAP serving size of some high fibre foods: (10).

Can I Eat Too Much Fibre?

A story reported by the Independent in 1998 sited a 51-year-old man who ate so much bran on a regular basis that it accumulated into a solid mass in his intestines and it had to be surgically removed. Bran contains vegetable fibres called phytobezoars which are useful to some animals but indigestible to humans and can build up into bezoars which can cause small bowel obstructions. (12)

Risk factors and causes of bezoars include:

- gastric surgery such as a gastric band (for weight loss) or gastric bypass (13)

- reduced stomach acid (hypochloridia) (13)

- decreased stomach size (13)

- disordered (16) or delayed gastric emptying, typically due to diabetes, autoimmune disorders, or mixed connective tissue disease (13)

- not chewing food properly, usually due to no teeth or poorly fitting dentures (13)

- an excessive intake of fibres (13), (15)

- eating too much fibre without consuming enough fluid (17)

It is to be noted that intestinal blockage is rare (14) and if you don’t have one of the risk factors for bezoars, you are unlikely to develop them. Reducing intake of foods with high amounts of indigestible cellulose may reduce the possibility for those who are at risk. (13)

What is considered to be “an excessive intake of fibres” ? Some people experience uncomfortable side effects from more than 70g of fibre a day, whereas others may experience this after just 40g (18). As discussed above, introducing too much fibre too fast can cause issues; additionally problems can arise from taking excessive fibre supplements, including weight loss pills. (21).

However, this information is to be balanced by the fact that human studies have concluded that fibre intake needs to exceed 50g per day to prevent colon cancer (19).

An article suggests that inhabitants of Mexico and Romania consume 93.6g and 88.1g of fibre per day respectively (20).

Additionally, fibre is highly important to our gut microbes. A fibrous diet:

- feeds our gut microbes helping them to thrive

- increases microbial numbers

- raises the number of different types of microbes in our guts

- thickens the mucus wall through the increase in bacterial population providing a protective barrier, lowering inflammation throughout the body

- aids digestion by the increase in bacterial numbers

The Hazda, a Tanzanian tribe, one of the last hunter-gatherer communities in the world, consumes a massive 100 grams of fibre a day from seasonally available foods. Their gut is packed with a large and diverse population of gut bacteria, which alters as their diet changes with the seasons.

The human race has been eating 100 grams of fibre every day for millions of years. As mentioned, some populations still have such a diet. Interestingly, it is these populations who don’t suffer from many of our chronic diseases. (25)

In summary, increase fibre slowly to understand your individual tolerance level, drink plenty of fluids, chew food well and be cautious if you have any of the conditions that might lead to intestinal blockage. I worked out that my own consumption is around the 100g to help my IBS-C. This may, in part, be due to the fact that I find it difficult to consume the variety of vegetables that I would like to without triggering IBS pain. Some vegetables have osmotic properties (by containing polyols) that draw water into the intestines to bulk out stools. To a certain extent, I rely on cereal fibres to do this work. I was also treated for SIBO (which I didn’t have, see: My Story) and the treatment severely attacked my microbiome. I am concerned that the extra fibre is making up for the loss of microbes, though I do have a redundant colon which can contribute to IBS-C. However, I surmise that I have always had this, but have never required this amount of fibre previously to keep me regular.

Phytic Acid And Fibre

Fibrous foods such as seeds, grains, legumes and nuts contain phytic acid in varying quantities with smaller amounts found in roots and tubers. Phytic acid forms phytates by binding with minerals in the body such as magnesium, iron, zinc and calcium. (26) (18) Humans don’t have the required enzymes needed to break phytates down meaning that some of these minerals pass through our small intestines without being absorbed (30), which could lead to nutrient deficiencies (18).

Phytic acid can reduce absorption of minerals from the meal within which they are consumed, but not subsequent meals. For instance, eating nuts as a snack may reduce the minerals absorbed from the nuts but not from the meal that you eat a few hours later. However, eating high phytate foods with most of your meals, may result in mineral deficiencies over time. (26)

Levels Of Phytic Acid & Phytase In Foods

Phytic acid levels of 400-800mg per day is fine for those with a diet rich in calcium, vitamin D, vitamin A, vitamin C, good fats and lacto-fermented foods. More than 800mg phytic acid per day is not a good idea. This means preparing phytic acid rich foods to reduce the content of phytic acid and restricting to two to three servings per day. When every meal contains more than one whole grain product, with an overreliance on nuts, legumes and wholegrains as a major source of calories, issues may arise. (29)

The general levels of phytic acid in different types of foods are discussed below:

- Bread: Heat generated from the industrial grinding of wheat and rye destroys phytase in addition to phytase becoming less over time. Ideally these should be freshly stone ground instead to ensure the phytase stays in tact. Sourdough fermentation with wheat or rye which contain high amounts of phytase works best for the reduction of phytates. For example in studies of sourdough fermentation:

- 4 hours at 92 degrees Fahrenheit reduced phytic acid of wheat by 60%

- 8 hours at 92 degrees Fahrenheit reduced the phytic acid of bran samples by 44.9%

- addition of malted grains and bakers yeast increased this reduction to 92-98 percent

- 8 hours for whole wheat bread showed almost complete reduction or even elimination of phytic-acid

- Rising bread by yeast alone may not completely reduce phytic-acid levels. Phytate breakdown is higher in sourdough bread than in yeasted bread. Since rye contains the highest amount of phytase, it is often used as a sourdough starter.

- Potatoes: Sweet potatoes and potatoes contain little phytic acid. (29)

- Oats: Since rye contains high levels of phytase that is activated during soaking, soaking oats with one or more tablespoons of freshly ground rye flour is ideal. Overnight soaking of oats alone improves digestibility, but won’t eliminate a huge amount of phytic acid. (29)

- Buckwheat: contains high levels of phytase and would not need added rye flour. (29)

- Legumes: Canned beans undergo processing such as soaking, blanching or pressure cooking at high heat for a short period. A study found that canned beans have lower phytate levels than dried, unsoaked beans. (33)

- Non dairy milks: Oat milk is high phytic acid. Hemp milk is lower in phytic acid. Many of the other milks such as soy and almond are high in phytic acid. (35) (36) (37). Hemp milk is available in supermarkets; there is also a recipe for hemp milk here: (34).

- Nuts: Soaking nuts can reduce phytate, but also reduces levels of minerals from the nuts leading to no overall improvement in the ratio of phytate to minerals. Therefore soaking does not increase nutrient bioavailability. (38)

- Quinoa: There is information about soaking quinoa here: (39).

The content of phytic acid in different foods in milligrams per 100 grams of dry weight is presented in the table below from The Weston A. Price Foundation (2010):

| Brazil nuts | 1719 |

| Cocoa powder | 1684-1796 |

| Brown rice | 12509 |

| Oat flakes | 1174 |

| Almond | 1138 – 1400 |

| Walnut | 982 |

| Peanut roasted | 952 |

| Peanut ungerminated | 821 |

| Lentils | 779 |

| Peanut germinated | 610 |

| Hazel nuts | 648 – 1000 |

| Wild rice flour | 634 – 752.5 |

| Yam meal | 637 |

| Refried beans | 622 |

| Corn tortillas | 448 |

| Coconut | 357 |

| Corn | 367 |

| Entire coconut meat | 270 |

| White flour | 258 |

| White flour tortillas | 123 |

| Polished rice | 11.5 – 66 |

| Strawberries | 12 |

The content of phytic acid in major cereals, legumes, oilseeds and nuts from Schlemmer et al. (2009) is found below:

| Name | Phytic acid g/100 g(dw) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals | ||

| Maize germ | 6.39 | Kasim and Edwards 1998 |

| Wheat bran | 2.1–7.3 | Harland and Oberleas 1986; Wise 1983 |

| Wheat germ | 1.14–3.91 | Wise 1983 |

| Rice bran | 2.56–8.7 | Kasim and Edwards 1998; Lehrfeld 1994 |

| Barley | 0.38–1.16 | Kasim and Edwards 1998 |

| Sorghum | 0.57–3.35 | Kasim and Edwards 1998 |

| Oat | 0.42–1.16 | Harland and Oberleas 1986 |

| Rye | 0.54–1.46 | Harland and Prosky 1979 |

| Millet | 0.18–1.67 | Lestienne et al. 2005 |

| Legumes | ||

| Kidney beans | 0.61–2.38 | Lehrfeld 1994 |

| Peas | 0.22–1.22 | Ravindran et al. 1994 |

| Chickpeas | 0.28–1.60 | Ravindran et al. 1994 |

| Lentils | 0.27–1.51 | Ravindran et al. 1994 |

| Oilseeds | ||

| Soybeans | 1.0–2.22 | Lolas et al. 1976 |

| Linseed | 2.15–3.69 | Wise 1983 |

| Sesame seed | 1.44–5.36 | Harland and Oberleas 1986 |

| Sunflower meal | 3.9–4.3 | Kasim and Edwards 1998 |

| Nuts | ||

| Peanuts | 0.17–4.47 | Venktachalam and Sathe 2006 |

| Almonds | 0.35–9.42 | Harland and Oberleas 1986 |

| Walnuts | 0.20–6.69 | Chen 2004 |

| Cashew nuts | 0.19–4.98 | Chen 2004 |

How To Reduce Phytic Acid

Methods used to reduce phytic acid content include:

- genetic improvement

- fermentation

- soaking

- germination

- enzymatic treatment of grains with phytase enzyme

Vitamin C reduces mineral losses such as iron from phytic acid. Harmful effects of phytates can be reduced by vitamin D and calcium. (29)

Phytase enzyme in some foods breaks down phytic acid. Foods that don’t contain sufficient amount of phytase to break down the phytic acid that they contain, include, for example:

- corn

- millet

- oats

- brown rice

Conversely, the following contain high levels of phytase:

- wheat with 14 times more phytase than rice

- rye with over twice as much phytase as wheat

Soaking or souring (with water and lemon juice or apple cider vinegar) in a warm environment, wheat and rye when freshly ground will destroy all phytic acid.

Steam heat will destroy phytase in ten minutes or less at about 176 degrees Fahrenheit or at 131-149 degrees Fahrenheit in a wet solution. For example, although high in phytic acid, all-bran cereal is heat processed and extruded into rod shapes, which will destroy all of its phytase. Heat treatment needed to produce commercial oatmeal will render the small amount of phytase in oats inactive.

Grinding too quickly or at too high temperature, freezing and long storage times destroy phytase. Freshly ground flour has higher levels of phytase than stored flour. Freshly grinding flour before use is common among traditional cultures. A study found that mice fed stored whole grain flours did not grow properly.

Phytic acid is not reduced by cooking alone. Souring (acidic soaking) for some time will activate the phytase to do its work of reducing phytic acid. This in addition to cooking will reduce a significant amount of phytate in grains and legumes. For example, eliminating phytic acid in quinoa involves fermenting or germinating plus cooking.

Micronutrient losses are minimized by lowering phytates ideally to 25mg or less per 100g or 0.03% of the phytate containing food.

Soaking To Reduce Phytic Acid

- The following should be soaked (or fermented) to reduce phytic acid: oats, rye, barley, wheat and quinoa. (32)

- Less frequently needing soaking: buckwheat, rice, spelt and millet (32)

- Not necessary to soak due to less phytates: whole rice and whole millet (32)

- No soaking if small amounts: flax seed (32)

- Soak oats for at least 12 hours at room temperature, in a slightly acidic medium, with phytase from whole wheat flour or buckwheat flour to break down the phytates. (40)

- Combine 1 cup rolled or steel cut oats with 1 cup water with 1 Tbs lemon juice, the water gently heated to around ~110 degrees. Add a Tbs or two (10%) of wheat flour and leave at room temperature 24 hours (or at least 12). Add another cup of water in the morning, bring to a boil and cook a few minutes until thick. (41)

- Add enough warm water to cover 1 cup of oats, add one tablespoon of whey, or one to two teaspoons of a dairy-free acid medium such as raw apple cider vinegar and one tablespoon of either rolled rye flakes (or rye flour or spelt flour) or if gluten free, use ground buckwheat groats. Soak at least 24-hours at room temperature. Drain oats and gently rinse. (42)

- Regarding acid for soaking, it is suggested that 2 tablespoon of acid per cup of oats or 1 tablespoon per half cup is too sour to consume. Some bypass the acid if using phytase rich rye or buckwheat. An alternative might be to try 1 to 2 teaspoon of acid to see if it is more palatable. (45)

There is further information on soaking grains here: (43) (44)

Do You Really Need To Reduce Phytic Acid?

Generally, we don’t consume completely raw and unprocessed grains and legumes. They would have undergone sprouting, cooking, baking, processing, soaking, fermenting, and yeast leavening. This means that the amount of phytates would be much lower by the time that we consume them. (48)

You probably don’t need to concern yourself with soaking grains if your diet is rich in minerals from meat, fish and vegetables. This may be more of a concern for societies who rely on grains and pulses with little to access other mineral rich foods. It may also be a concern for vegans and vegetarians who rely on grains and pulses due to absence of meat, fish, eggs and milk. With a nutrient dense, omnivorous diet, the mineral binding capacity of phytic acid is unlikely to lead to mineral deficiency. However, eating sourdough or soaking or sprouting grains may make them easier to digest, if needed. (47)

Here are some points from a study to find out whether reducing phytate level of wholemeal rye bread increased iron uptake in women:

- the first 10–20 mg of phytate in a meal exerts the largest inhibitory effect on iron absorption

- phytate beyond 10-20mg in a meal has a relatively minor effect on iron availability

- although the women were consuming low phytate bread, phytates from other sources in their diets would have nullified the effect on iron bioavailability

- an 8 week high phytate diet had no effect on ferritin (iron), transferrin receptor (aiding uptake of iron), and hepcidin (hormone that regulates how your body uses iron) concentrations in 28 females

- those consuming the low phytate bread had an unexpected decrease in iron markers, which was strange due to the total wholegrain intake did not change during the study. However there may have been a shift in dietary iron inhibiters and enhancers during the study to explain this

- although, single meal studies show that reducing phytic content of that meal shows an increase in iron bioavailability, medium term consumption of phytate reduced bread under normal eating conditions is not sufficient for improving iron status

- with a mixed diet, adding additional wholegrains to the diet does not adversely affect iron status even if the diet is already high in wholegrains

Health Benefits Of Phytic Acid

Although iron performs vital functions in the body, it can contribute to free radical formation when your body’s regulation of iron is disrupted. Phytic acid binds with iron so that you don’t fully absorb iron from grains. Researchers see this mechanism as phytic acid acting as an antioxidant. Phytic acid not only binds with iron but also binds with heavy metals in the gut reducing their accumulation in the body. Linked with this, researchers are examining phytic acid’s role in reducing colon and other cancers. (47)

There is an ongoing study regarding the use of phytic acid in improving the health of the microbiome. The study discussed the fact that iron is not absorbed very well in the small intestine, so much of it travels to the large intestine. The large intestine contains trillions of bacteria. Some bacteria can use iron as food and this includes bad bacteria (such as Enterobacteria) which are harmful to health. Many good bacteria such as Bifidobacteria can survive without iron. This means that phytic acid can be used to reduce iron getting into the large intestine, reducing the feed for iron consuming bad bacteria. Without this limiting effect, the large intestine could become populated with more bad bacteria than good bacteria. In the study participants will consume a capsule of either phytin (a salt form of phytic acid) or an inactive substance. The researchers are interested in whether the phytin reduces the number of Enterobacteria (bad bacteria) in the large intestine. (50)

Health Benefits Of Fibre

Butyrate, which is important for health is generated by good bacteria in the gut by digesting fibre. Conversely, bad bacteria can lead to inflammation, chronic diseases and resist antibiotics. It is very important for health to have these bacteria in balance. Fibre can help keep this balance by promoting good bacteria in the gut and thus help protect against disease. (58)

Further Reading And References

(6) Ryan Raman, MS, RD: 14 Healthy Whole-Grain Foods (Including Gluten-Free Options), healthline.com, Updated on February 24, 2023

(9) The Association of UK Dietitians: Fibre

(12) Roger Dobson: Now bran can be bad for you, INDEPENDENT, 29 March 1998

(14) Milosevic, S.; Kovac, J.D.; Lazic, L.; Mitrovic, M.; Stosic, K.; Basaric, D.; Tadic, B.; Stojkovic, S.; Rasic, S.; Ivanovic, N.; et al. “Bezoar Egg”—A Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14040360

(16) ANDREW WEIL, M.D: Bezoars: A Digestive Dilemma?, SEPTEMBER 25, 2009

(20) Dr Robert Barrington: The Fibre Intake of Various Countries, June 25 2014

(21) Annie Price, CHHC: How Much Fiber Per Day Should You Consume?, draxe.com, July 31, 2023

(23) Olga Khazan: Just Eat More Fiber, JANUARY 9, 2018

(25) Michael Greger M.D. FACLM: Eating the Way Nature Intended, NutritionFacts.org, March 5th, 2019

(29) RAMIEL NAGEL: Living With Phytic Acid, The Weston A. Price Foundation, MARCH 26, 2010

(30) Kylie Hollonds: What is Phytic Acid in Oats?, GF Oats

(34) RHIAN STEPHENSON: Hemp milk recipe, Women’s Health, 03/04/2014

(39) PATRICIA CARTER: PREPARE SOAK QUINOA, BIOME ONBOARD AWARENESS, MARCH 17, 2016

(40) Kitchen Stewardship®: Are “Overnight Oats” Traditional? Are They Safe?

(42) Kelly: How to Soak Grains for Optimal Nutrition, The Nourishing Home

(43) MyLongevityKitchen: The Truth About Overnight Oats, November 28, 2016

(45) Kelly: Soaked Oatmeal (Gluten-Free), The Nourishing Home

(52) prebiotin.com: Fiber Content of Foods